Regulatory Compliance: The Necessary Evil

Complacency or an attitude of "compliance is good enough" can set in when compliance is the only management message.

- By Brian D. Rains

- Jul 01, 2014

In 1967, psychiatrists examined the medical records of more than 5,000 medical patients as a way to determine whether stressful events might cause illnesses. Patients were asked to tally a list of 43 life events based on a relative score. Their results were published as what is commonly known today as the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale. Seven of the "Top 10 Life Events" are listed here, plus their relative "Life Change Units," or stress units, as published in Wikipedia:

Life Event

|

Life Change Units

|

Death of a spouse

|

100 |

| Divorce |

73 |

Marital separation

|

65 |

| Imprisonment |

63 |

Death of a close family member

|

63 |

Personal injury or illness

|

53 |

| Marriage |

50 |

Number 8 on this list, right below marriage but well below divorce (at number 2), is "dismissal from work." Although I was not technically dismissed from my work, nor did I experience a divorce, in 2004 I did experience significant stress when I was part of a business unit divestiture. Overnight, I went from working for a company that I had been with for nearly 23 years to a new company. In many ways, it felt like a dismissal and/or a divorce.

As I have analyzed the component parts of the stress associated with this change, differences in corporate culture were the main culprits.

The different cultures were understandable. My former company was large, with millions of shares being traded publicly every day. The board of directors consisted of all external, non-employee directors. The CEO was rotated every five to 10 years. My new company was even larger, but ownership was concentrated within a few family members who also served as the board of directors and as the company’s CEO and executive vice president. They had held these positions for decades. Decision-making, ownership, and culture originated with the very few, most senior leaders.

Not surprisingly, nowhere were the two cultures between these companies more different than in their approach to compliance.

In my former company, rarely was the term regulatory compliance mentioned. We had strong corporate standards and expectations. We pursued a "Goal of Zero" with passion. There was a strong accountability culture in place. Without its being explicated stated, regulatory compliance was something that just "happened" by following the corporate rules. I had even been introduced to the concept of assuming (or choosing) "regulatory compliance risk" as a possible business alternative.

In my new company, a strong Compliance Culture existed. This was communicated by the new company's leaders even before the official sale was completed. Everyone was expected to comply all of the time. And they meant it--there was no margin for error. Needless to say, this added significant employee stress as we adjusted to this new, stark reality.

Compliance began with regulatory compliance. Tremendous effort was placed on fully understanding all applicable regulatory requirements. Training was conducted. Audits were performed. Systems were instituted to track new and emerging regulatory requirements. But it didn’t stop there. Compliance with corporate standards was also an expectation, as was compliance with local site procedures.

Individuals who could not, or would not, live up to the expectations associated with the Compliance Culture looked for work elsewhere. Living through this abrupt transition in corporate culture, with particular emphasis on compliance, led me to the observations that are summarized in the title for this paper: Regulatory Compliance, A Necessary Evil.

I firmly believe that both of these approaches to compliance have both merit and pitfalls. There are strengths and weaknesses of both. For clarity, I will call one culture a "Compliance Culture" and the second "Goal Zero."

Pros and Cons: Compliance Culture

Regulatory compliance is not optional. It must be a given. In a very real sense, license to operate potentially dangerous facilities is granted to companies from governments that are obligated to provide for and protect the welfare of their citizenry. Laws are enacted and enforced by governments in the discharge of these obligations and duties.

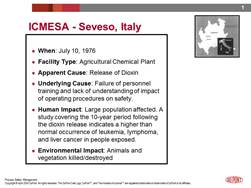

The history of process safety regulations has clearly been in direct response to catastrophic incidents. The Seveso regulations in the European Community were some of the first process safety regulations enacted by any governmental body. The regulation’s common name comes from the small town in Italy, Seveso, where a significant process safety incident occurred in 1976. A few of the details are found below.

In the United States, a similar pattern exists. In fact, in its September 1992 "Compliance Guidelines" directive regarding compliance with 29 CFR 1910.119 regulations, better known as the PSM Regulations, OSHA stated that:

“In recent years, a number of catastrophic accidents in the chemical industry have drawn attention to the safety of processes involving highly hazardous chemicals. OSHA has determined that employees have been and continue to be exposed in their workplaces to the hazards of releases of highly hazardous chemicals which may be toxic, reactive, flammable, or explosive.

The requirements of the PSM standard are intended to eliminate or mitigate the consequences of such releases. The standard emphasizes the application of management controls when addressing the risks associated with handling or working near hazardous chemicals."

A similar pattern of regulatory reactivity and response has evolved in the upstream oil & gas compliance environment following the April 2010 Deepwater Horizon incident in the Gulf of Mexico.

Indeed, regulatory compliance is not optional.

Regulatory compliance brings with it many benefits. Most benefits have to do with image and perception in the "court of public opinion," including:

- Building stronger credibility with regulators and government representatives

- Establishing a stronger basis for trust with local communities; preserves a facility's "right to operate"

- Helping to avoid fines and helps prevent other court action and the potential negative financial impact

- Helping to prevent reputational loss

The primary challenge for organizations that adopt a compliance-only orientation is that regulatory compliance will not necessarily ensure or even improve the organization’s process safety performance. Complacency or an attitude of "compliance is good enough" can set in when compliance is the only management message. I will use a simple example to illustrate.

I believe all responsible operators of hazardous materials would agree that we are all still on a learning curve with respect to PSM excellence. Since 2007, the DuPont Corporate PSM Standard has been amended three times to reflect new knowledge gained from our own incidents, plus those from industry in general. Excellence in PSM requires a continual learning culture to drive continuous improvement. But yet the Seveso Regulations have gone through only one significant rewrite in their history, and the U.S. OSHA regulations have not been formally amended a single time in the 22 years since they were issued. If an organization is relying on the regulations to keep pace with the ever-changing and improving field and science of process safety management, I expect that its results will be inferior vs. its peers and will very likely be unacceptable.

I don't believe even the regulators believe that total compliance only with the existing regulations will yield zero (or maybe even top quartile) process safety incidents performance.

A Compliance Culture does have a distinct impact on the overall management-to-employee dialogue and relationship. As intended, a Compliance Culture leaves little room for interpretation as to what is expected of employees and their behavior. This can be a positive from an operational discipline perspective and can produce very consistent and reliable performance. However, the opposite also is possible when such a rigid standard causes an increase in unsatisfactory performance discussions up to and including terminations. An organization can quickly become demoralized when such activity highlights negative performance and the loss of experience and esprit de corps.

My Compliance Culture observations are summarized in the following table.

Compliance Culture: Strengths

|

Compliance Culture: Challenges

|

#1 Builds stronger credibility with regulators and government representatives

|

#1 Can create a sense of complacency that "compliance is good enough"

|

#2 Establishes a strong basis of trust with local communities; preserves a facility's "right to operate"

|

#2 Can place undue emphasis on compliance as the means to achieve excellent process safety performance

|

#3 Avoids fines and other and helps prevent other court action and the potential negative financial impact

|

#3 Can be demoralizing when such a strict "black and white" interpretation of individual performance is fully implemented

|

#4 Helps prevent reputation loss in the public's eye

|

|

| |

|

Pros and Cons: Goal Zero

Most organizations and companies express their commitment to safety and process safety management excellence using the word "zero" or something similar, as seen below using examples from DuPont, Chevron, ExxonMobil, Dow Chemical, plus others.

- Zero Harm to People or the Environment

- No accidents, injuries or harm to the environment

- Committed to Zero

- Zero is Attainable

- Zero Fatalities

- Zero Incidents Period (or ZIP)

- Nobody Gets Hurt

Needless to say, these statements of aspiration and direction are easier to articulate and communicate than they are to realize and achieve. But I believe we must applaud these organizations for making these statements during a period when catastrophic incidents continue to occur. In other words, these statements are made when, in many cases, how they are to be realized is not fully understood.

This speaks to the most important positive aspect to the Goal Zero Culture. Goal Zero drives the right behaviors:

- It drives a learning culture that is always attempting to learn and not repeat mistakes.

- It drives innovation and creativity in the pursuit of new ways to improve and reduce incidents.

- It drives greater involvement and engagement among all levels in the organization. (Who benefits when incident performance improves? Everyone!)

- It drives greater line management accountability for improving results at all levels.

One also could argue that even beyond the business benefits Goal Zero may yield, it is simply the right thing to do. Injury to individuals and/or the environment is increasingly intolerable across the globe … and it should be. No organization has the right to inflict such damage.

There are some potential challenges to a Goal Zero pursuit, however. The first is that with such lofty aspirations and objectives, the organization may lose sight of how important regulatory compliance is. A certain type of arrogance and malaise can set in. Individuals can erroneously conclude that their work is on “a higher plane” than mere compliance. They may choose to not dedicate the necessary time and effort to stay abreast of changing regulatory requirements or the effort to be in full compliance.

A second potential challenge, and often the more difficult one, is the issue of stakeholder expectations management. When organizations publicly declare their intentions to pursue "Goal Zero" objectives, sometimes the associated timetable for that pursuit gets lost or drowned out. It is only human nature that people assume that if Goal Zero is possible, then, “Why not now?" Why should I have to wait? What can be done to accelerate progress? And then, if an incident does occur, trying to put the event in context of the long-term objective can be very difficult.

A very current example of this is the debate under way in California about the potential benefit of the Safety Case Regime. An incident did occur at a company facility that embraces the Goal Zero ideal. Perfection, however, has not yet been achieved. I believe that with all good intentions, the community and governmental organizations are demanding improvement. But changing the status quo does not necessarily yield improvement. The company is spending considerable resources managing the expectations of its many stakeholders, both external and internal. Is this inappropriate? No, but it surely has the potential to divert attention away from efforts to identify and eliminate the root causes of the incident itself.

My Goal Zero observations are summarized in the following table:

Goal Zero: Strengths

|

Goal Zero: Challenges

|

#1: Drives greater line management accountability for improve results

|

#1 Can lead to arrogance and organization indifference for regulatory requirements

|

#2 Has the potential to achieve process safety performance what a compliance-only approach may achieve

|

#2 Can create an impression in smaller jurisdictions, where regulatory support may be limited, that a complete, local understanding of the law is not essential

|

#3 Creates a culture of greater creativity, involvement, an employee ownership in the pursuit of excellence

|

#3 Managing expectations is a much bigger challenge as governments, the public, and even employees assume that Goal Zero mean it is achievable now!

|

#4 Encourages a learning culture in support of continuous improvement

|

|

Conclusion

Regulatory compliance is not optional, regardless of the country or jurisdiction. Too much of a business’s long-term future is at risk for any organization to demonstrate disdain for the law and its compliance. But the limitations of adopting a PSM performance objective based only on regulatory compliance must be recognized and rejected.

Compliance will not lead companies interested in long-term viability to a level of process safety performance that all of their stakeholders will expect and accept. A balanced approach that embraces both a regulatory compliance imperative as the minimum essential but drives beyond and further toward zero process safety incidents is the only truly sustainable approach to process safety management.

This article originally appeared in the July 2014 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.